A compiler is usually consists of a frontend and a backend that work with each other through intermediate representation (IR). The frontend is responsible for converting the program text in language A (e.g. C, Go, Rust) and convert it into an IR that is understood by the compiler backend. A very popular compiler infrastructure is LLVM and it provides a rich IR language. This is a great tool to build toy compilers (and large-scale as well).

Once the IR is generated, the backend reads the IR and produces machine code for a particular platform (hardware). This separation of frontend and backend allows independent development of both. In this post, I'll focus on the frontend part of the compiler, and later use LLVM tools to use the generated IR to generate executables.

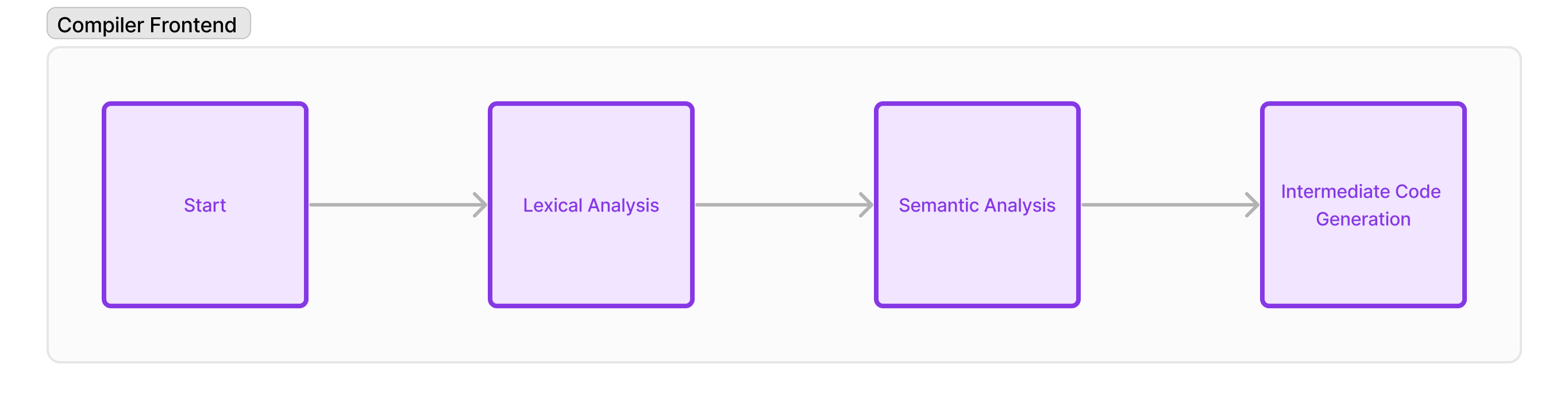

Parts of a compiler frontend #

A compiler frontend majorly consists of three parts:

-

Lexical Analysis (a.k.a. scanning): This part reads the input program text character by character and produces a list of "tokens" that are recognised by the compiler. E.g. a program text

1 + 1;in an arithmetic expression is converted toLITERAL(1), OPERATOR(+), LITERAL(1), SEMICOLON. -

Semantic Analysis: This part receives the tokens from the first part and builds a syntax tree as per the language semantics. E.g.

LITERAL(1), OPERATOR(+), LITERAL(1), SEMICOLONgets converted into a tree structure as such:

-

Making Sense of the Syntax Tree

- (Option 1) Intermediate Code Generation: This option takes in the syntax tree from part 2 and generates the IR code, similar to how compiled languages are translated to IR.

- (Option 2) Interpreting and executing code: In this option, the code is executed from the syntax tree. This is similar to how interpreted languages like JavaScript and Python work.

For this session, we'll take the example of a simple language ccc-lang and build an interpreter for it. Generation of IR will be discussed in later parts. The language allows writing expressions, assigning variables and declaring and using functions. Since it is simple, there are several restrictions as compared to full-fledged languages. Some include:

- Functions are single-lined - the value returned by the line is immediately returned.

- Arithmetic - only addition and subtraction is allowed to limit the complexity of priority. Arithmetic expressions have only two operands. (bigger expressions can be composed though)

- Literals are only integers.

Full implementation: https://github.com/mohitk05/ccc-lang/

Following are some example programs in ccc-lang:

let a = 1;

print(a);

let a = 1;

let b = a + 2;

print(b);

function add(a, b) {

a + b

}

let a = 1;

let c = 2

let sum = add(a, c);

print(sum);

function add(a, b) { a + b };

let a = 1;

let c = 3;

let b = add(a, c);

print(b);

function sub(a, b) { a - b };

let d = sub(c, a);

print(d);

Structure of the session:

- We'll first try to build a simple interpreter for addition expressions

- Then we'll add subtraction

- We go one step further and introduce variables

- Let's look at functions? Simple library functions like print

- User-defined functions (if time permits)

But you may choose a language of your own to implement! Here are some for starters:

- A boolean expressions language (e.g. evaluating expressions like

true && false || false || true) - An emoji-based language, no more ASCII characters! (e.g.

💃(⚡️)) - LISP-like languages (e.g.

(+ 1 2 3)) - A pipe-system (e.g.

1 | echo,"hey" | reverse | double // prints "yehyeh")

Parser Expression Grammar #

We'll be using pest - a parser-generator for Rust. It uses PEG to generate parsers automatically. All we have to do later is to then handle the generated parse tree.

Head over to https://pest.rs, we'll try writing some grammar for our first iteration of the language.

Simple Addition #

Addition expressions look like

1 + 2 + 3 + ...

Let's try to break it down into smaller problems and tackle them one at a time. Let's write some PEG for addition operation that only supports two operands, e.g. 1 + 2 or 22 + 33. One important terminology here is terminals and non-terminals. When we try to break down the program text into meaningful tokens and rules, we will have entities that make up the leaf nodes of the syntax tree - known as terminals, while others are made up of more non-terminals or terminals - known as non-terminals. E.g. a digit is a terminal and something like an addition expression 1 + 2 is a non-terminal in our language.

PEG is made up of rules and their definitions. Pest has a particular syntax to write PEG that we'll become familiar of, as a hint, it has similar elements as in regular expressions. PEG is like regex but more powerful. Let's start with the grammar for a two-operand addition expression:

// lang.pest

addition = { ASCII_DIGIT ~ "+" ~ ASCII_DIGIT }

Pest provides some pre-defined rules to help with writing grammars. ASCII_DIGIT is one such rule that matches an ASCII digit i.e. [0-9]. A rule is written as:

rule_name = { definition }

The ~ sign denotes ordering in Pest. It means that Pest will match the pattern to the right of the ~ only if the left side matches. So for the addition rule, if the left part is not a digit, the parser will exit the rule and try another one, and addition won't be the matched rule.

Any literal can be written in double quotes - here the plus sign is written as +.

Let's try to test if this grammar works. Go to https://pest.rs and scroll down to the grammar editor and paste the grammar above. Then in the input, enter an example addition expression. On the right you should see a tree representation of what Pest parsed and the corresponding rule types for the matching text.

You should see something like - addition: "1+2". Note that if you include spaces between the characters the parsing fails! This is expected because we haven't mentioned to Pest anything about how to handle whitespace. Usually, whitespace is something you would ignore while parsing, unless you use it to build scopes (e.g. Python). Our language uses { } to denote scopes so we can safely ignore any whitespace. Add the following line to your grammar - the _ at the beginning of the definition tells Pest to not to produce representations for those rules.

WHITESPACE = _{ (" "|NEWLINE) }

Generalising addition of infinite number of operands #

Now that we have successfully parsed addition expressions with two operands, we can extend the rule to include infinite operands. Ideally that is what we would want in our language - the ability to add any number of operands. To implement this, we'll use a special syntax that you might find similar to regular expressions, the difference being that you can apply it to complex rules. This syntax is foundation to writing complex grammar rules for our language.

Before moving forwards, let's quickly address one issue with our current grammar. Since the operands are being represented by ASCII_DIGIT, it tells Pest to match only a single digit for operands and operands with more than one digits will not be parsed correctly. To solve this issue, we'll use the + notation to signify that an operand can be made up of one or more digits.

addition = { ASCII_DIGIT+ ~ "+" ~ ASCII_DIGIT+ }

Back to generalising addition. If you look at an addition expression, and try to find a pattern, you'll quickly see that it can be represented as follows:

1 + 2 + 3 + ...

=

operand (+ operand) (+ operand) (+ operand) ...

The pattern + operand repeats multiple times as long as the expression is. This can be written in PEG as follows. To make it easy to group operands, let's create a new rule to denote operands.

addition = { operand ~ "+" ~ operand }

operand = { ASCII_DIGIT+ }

The generalised addition rule looks like follows:

addition = { operand ~ ("+" operand)* }

operand = { ASCII_DIGIT+ }

The * notation means that the ("+" operand) pattern can be present zero or more times. This nicely covers our case for generalised addition. Paste this in the grammar editor on https://pest.rs and try a longer addition expression.

Now, let's quickly also include subtraction in our language. Currently the + operator is a terminal in our grammar, we need a rule to denote an "operator". Let's create one.

addition = { operand ~ (operator operand)* }

operator = { "+" | "-" }

operand = { ASCII_DIGIT+ }

As you might have guessed, the | notation is to denote an ordered union - meaning the patterns will be checked in order and the first one to match will be chosen.

Multi-line programs #

So far we have been parsing a single line of text. Usually, programs are multi-line with various kinds of statements - variable and function declarations, function calls, expressions like arithmetic, conditionals etc. To support all of these, we first need to support multi-line programs. A common way is to create a root rule named program and compose it with multiple statements. Each statement can then be one the types mentioned above. Let's use the notations we learnt in the previous section to define program and statement rules.

program = { statement+ }

statement = { addition ~ ";" }

The grammar above says that a program can be one or more statements and a statement can be an addition expression followed by a semicolon. That's how we want to denote end of a line in ccc-lang.

Let's try to also generalise statement so that when we add more expressions (other than addition), we'll have room for those.

statement = { expression ~ ";" }

expression = { addition }

We created a new rule called expression to group all kinds of expressions. Expression, in our language, is a pattern that results in a value. Some examples of expressions are arithmetic, conditionals, function calls, boolean expressions.

Let's try statements - "lines in a program".

1 + 2;

3 + 2;

4 + 3 + 4;