I have been using oxlint in some of my personal projects and I love the speed and DX it offers over traditional ESlint for linting TypeScript files. It is part of the project oxc which is building a set of JavaScript tooling in Rust - ranging from a parser, bundler, linter, resolver and formatter. I decided to try my hand at contributing back to the project by picking a good-first-task and also brush up my compiler skills on the way. The PR is still in progress, but I want to document my though process here - so this may go over a single post eventually.

The rule - no-useless-assignments #

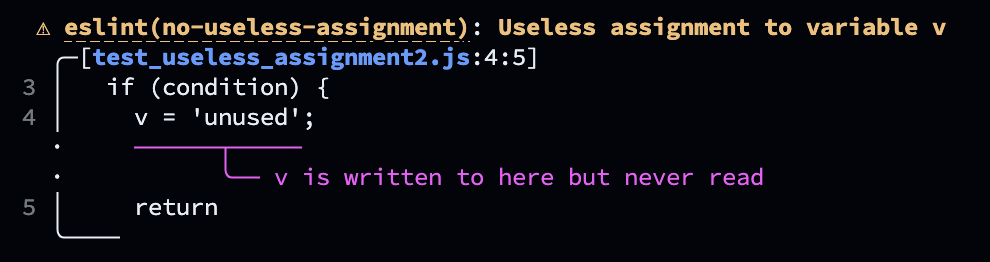

ESlint docs do a very good job in describing what the rule should catch.

The rule should detect any occurrences of assignments made in code that are never used later. By "used" it means "read". That is if there is a write to a variable and no read happens afterwards, that assignment is useless and can be removed. These are called dead stores in programming and often indicate a code smell and are bad anyway as they waste processing power and memory.

Some examples from the ESLint docs where the rule should fail a lint check:

function fn1() {

let v = 'used';

doSomething(v);

v = 'unused';

}

function fn2() {

let v = 'used';

if (condition) {

v = 'unused';

return

}

doSomething(v);

}Examples of correct code:

function fn1() {

let v = 'used';

doSomething(v);

v = 'used-2';

doSomething(v);

}

function fn2() {

let v = 'used';

if (condition) {

v = 'used-2';

doSomething(v);

return

}

doSomething(v);

}Approaching the problem #

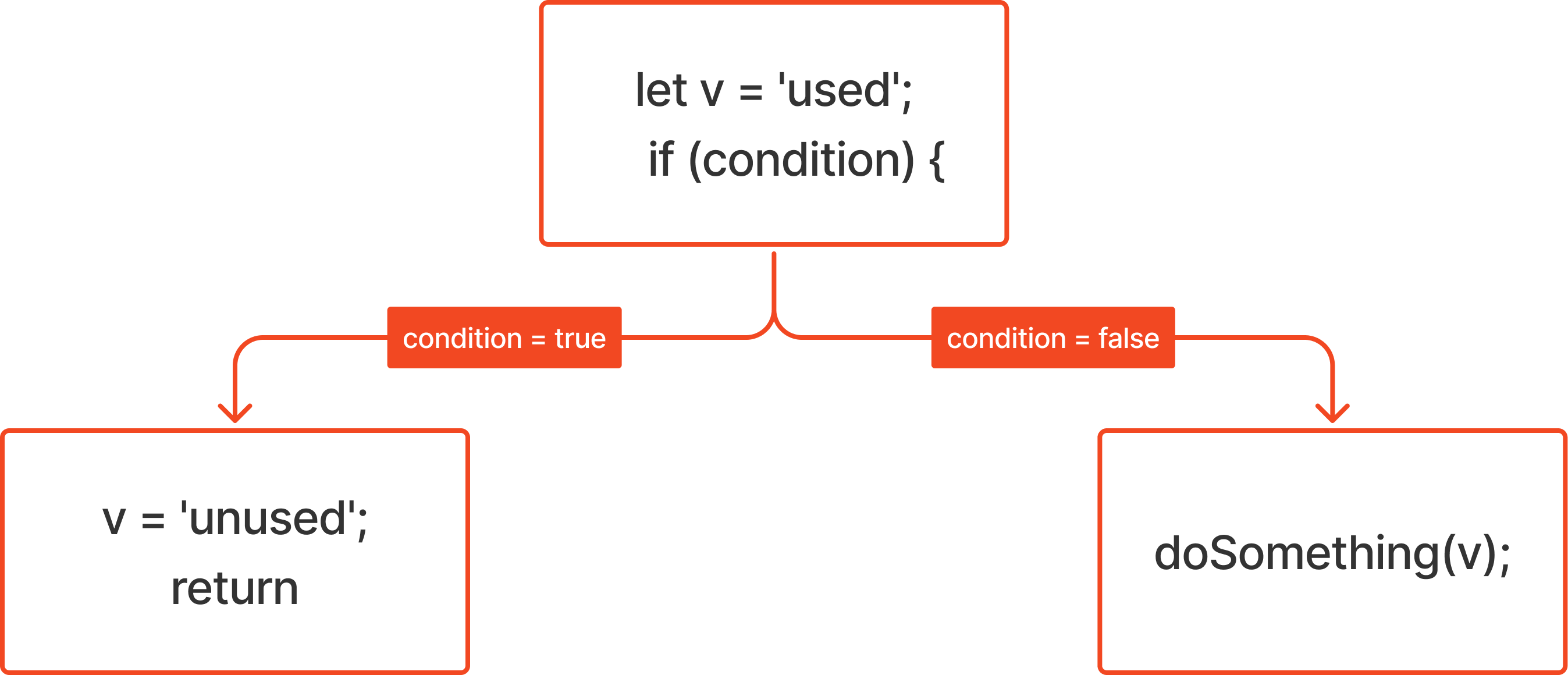

Looking at the examples and different cases that have to be handled, I initially thought of tracking the read and write references for a variable and then detect if there is a write immediately after a previous write. While this works for simple use cases, this fails when the variable usage spans across multiple scopes. The eventual idea I arrived at was using the control-flow graph (CFG).

A CFG is a graph representing how control flows in the program. Control changes via statements like if..else, return, for, break, continue etc., essentially anything that changes the flow of your program from a sequential execution to a jump to a different position.

E.g. in this program:

function fn2() {

let v = 'used';

if (condition) {

v = 'unused';

return

}

doSomething(v);

}There are 3 blocks here such that all statements in a "block" execute sequentially.

The branching occurs at if(condition) and the control flow may go to the left block if it is true or to the right if it is false. Now, to detect useless writes, we would have to check:

- If a write has at least one read after it (via any control flow path) that uses it

- There is no write before such a read is found

The whole logic can be divided into two cases: for reads and writes in the same vs. different blocks. The oxc project has a oxc_cfg crate which exposes a CFG API to work with the control flow graph constructed during the semantic phase of the linter. A linter is almost a compiler, it just does not produce any code. oxlint has a trait called Rule that every custom rule implements. It has methods that let a rule implementor run logic at various triggers, following the visitor pattern.

Detecting unused assignments #

The run method runs for each node in the abstract syntax tree (AST). A different method called run_once runs once and can be used to run a global pass for the entire tree. This is what would be useful for the no-useless-assignment rule as we want to use the CGF and not depend on the node relations in the AST, which would be the case with the run method.

The logic on a high-level would be:

For each variable

- Get list of all reads and writes for this variable

- For each write, check subsequent reads and writes. If there is a write before a read is encountered, keep a note of it. We don't want to mark the first write as useless yet as there could be a read in a different path that uses it.

- If a read is encountered and if the read is reachable from the write, check if there was any write encountered on the way.

- If there was none, mark the first write as used and move to the next one.

- If there was a write seen in step 2, check if the read cannot be reached from this write. If this is true, it means that the first write is used by this read without being overwritten by another write in between.In the run_once method we get access to various context from previous passes on the AST. One such information is a list of references to a symbol. With this list, we can start implementing the above logic for each variable in the program and create a global pass for the rule.

impl Rule for NoUselessAssignment {

fn run_once(&self, ctx: &LintContext) {

let cfg = match ctx.semantic().cfg() {

Some(cfg) => cfg,

None => return,

};

let nodes = ctx.nodes();

let scoping = ctx.scoping();

for node in nodes {

match node.kind() {

AstKind::VariableDeclarator(_) => {

let declarator = node.kind().as_variable_declarator().unwrap();

let Some(ident) = declarator.id.get_binding_identifier() else {

continue;

};

let symbol_id = ident.symbol_id();

let references: Vec<&Reference> =

scoping.get_resolved_references(symbol_id).collect();

if references.is_empty() {

continue;

}

analyze_variable_references(ident, &references, node, ctx, cfg);

}

_ => continue,

}

}

}

}The code above defines a loop for all nodes in AST and matches all VariableDeclarator nodes to run the usage checking logic. This line gives the list of all resolved references to the symbol ID corresponding to the variable.

let references: Vec<&Reference> =

scoping.get_resolved_references(symbol_id).collect();Handling initialization and assignments #

Oxc's AST handles initialization and assignments a bit differently. References to a variable do not include the initialization and hence I'd have to handle it separately. Well, this is a great place to use Rust's sum types using enums!

The core idea is to run the logic for each write and pass the index of this write to a function that can then process subsequent reads and writes. For initialization though, I want to process all the references, as they are the subsequent references (if you think of initialization as yet another write reference at -1th index). The analyze_variable_references function looks like:

enum ReferenceIndex {

NonInit(usize),

Init,

}

fn analyze_variable_references(

ident: &BindingIdentifier,

references: &[&Reference],

decl_node: &AstNode,

ctx: &LintContext,

cfg: &oxc_cfg::ControlFlowGraph,

) {

let nodes = ctx.nodes();

let has_init =

decl_node.kind().as_variable_declarator().and_then(|d| d.init.as_ref()).is_some();

if has_init {

let init_cfg_id = nodes.cfg_id(decl_node.id());

check_write_usage(

ident,

references,

ReferenceIndex::Init,

init_cfg_id,

decl_node.span(),

ctx,

cfg,

);

}

for (i, reference) in references.iter().enumerate() {

if !reference.is_write() {

continue;

}

let write_cfg_id = nodes.cfg_id(reference.node_id());

let assignment_node = nodes.parent_node(reference.node_id());

let write_span = assignment_node.span();

check_write_usage(

ident,

references,

ReferenceIndex::NonInit(i),

write_cfg_id,

write_span,

ctx,

cfg,

);

}

}Btw, I love Rust's pattern matching and sum types, it has changed how I look at combining types and handling them!

Working with the references #

Now the meatier part is inside the check_write_usage function. This has the core logic using the control flow graph. A CFG, as any graph, has nodes and edges. The code for oxc_cfg has various methods, some of which are relevant here:

pub struct ControlFlowGraph {

pub graph: Graph,

pub basic_blocks: IndexVec<BasicBlockId, BasicBlock>,

}

impl ControlFlowGraph {

pub fn graph(&self) -> &Graph {}

pub fn basic_block(&self, id: BlockNodeId) -> &BasicBlock {}

pub fn is_reachable(&self, from: BlockNodeId, to: BlockNodeId) -> bool {}

pub fn is_cyclic(&self, node: BlockNodeId) -> bool {}

}I initially thought of traversing the graph using the cfg.graph.neighbors() method, going over each path but thanks to Claude Code, it suggested using the is_reachable method instead. It's actually very easy this way - instead of checking on each path, we just check at the reference and see if there is a path between two using is_reachable()!

// Inside check_write_usage()

let mut assignment_used = false;

let mut last_reachable_write: Option<&Reference> = None;

for r in references_after.iter() {

if r.is_write() && cfg.is_reachable(write_cfg_id, nodes.cfg_id(r.node_id())) {

last_reachable_write = Some(r);

continue;

}

if r.is_read() && cfg.is_reachable(write_cfg_id, nodes.cfg_id(r.node_id())) {

if last_reachable_write.is_none() {

assignment_used = true;

break;

}

if let Some(last_reachable_write) = last_reachable_write {

if !cfg.is_reachable(

nodes.cfg_id(last_reachable_write.node_id()),

nodes.cfg_id(r.node_id()),

) {

assignment_used = true;

break;

}

}

}

}Handling loops #

Loops need some special handling. for has an update expression which updates the iterator variable for the next iteration. The rule might mark this as an unused variable if it is not used internally, but in fact it is used in the condition expression of the for loop.

for(let i = 0; i < 10; i++) { // i++ is "useless", but is infact

// used to evaluate i < 10 in next iter

console.log("Hello")

}I added a condition to catch this:

if !assignment_used {

let references_before = match idx {

ReferenceIndex::NonInit(i) => Some(&references[..i]),

ReferenceIndex::Init => None,

};

if let Some(references_before) = references_before {

if cfg.is_cyclic(write_cfg_id) {

for r in references_before.iter() {

if r.is_write() {

continue;

}

if cfg.is_reachable(write_cfg_id, nodes.cfg_id(r.node_id())) {

assignment_used = true;

break;

}

}

}

}

}Here, I get a slice of references before the write in question (e.g. i++). I check if the basic block where the write happens is cyclic, i.e. the control may come back to the block via itselt. This means this is a loop block. In this case, check if there is a read before the write and if the read is reachable from the write. In this case the assignment is actually used.

Wrapping up #

Well, it took a lot of time for me to arrive at this final implementation. It is especially hard to work with APIs in an already established project, but once I got grasp of it, things made a lot of sense. The oxc project is well structured and I love the abstractions, e.g. the diagnostic reporting tool produces beautiful logs and as a rule developer you only have to pass a node "span".