Most of us are aware of the popular methods of traversing a graph data structure - depth first search (DFS) and breadth first search (BFS). DFS goes to the deepest levels of the graph and then covers the breadth while BFS covers the breadth with gradually going deep.

Usually when I come accross a problem that looks like a graph, e.g. parsing a JSON structure, traversing nodes in a DOM element, DFS seems like a natural solution as it is recursive in nature and has a declarative implementation. This is a very personal opinion I should say, as both the methods have their own application areas.

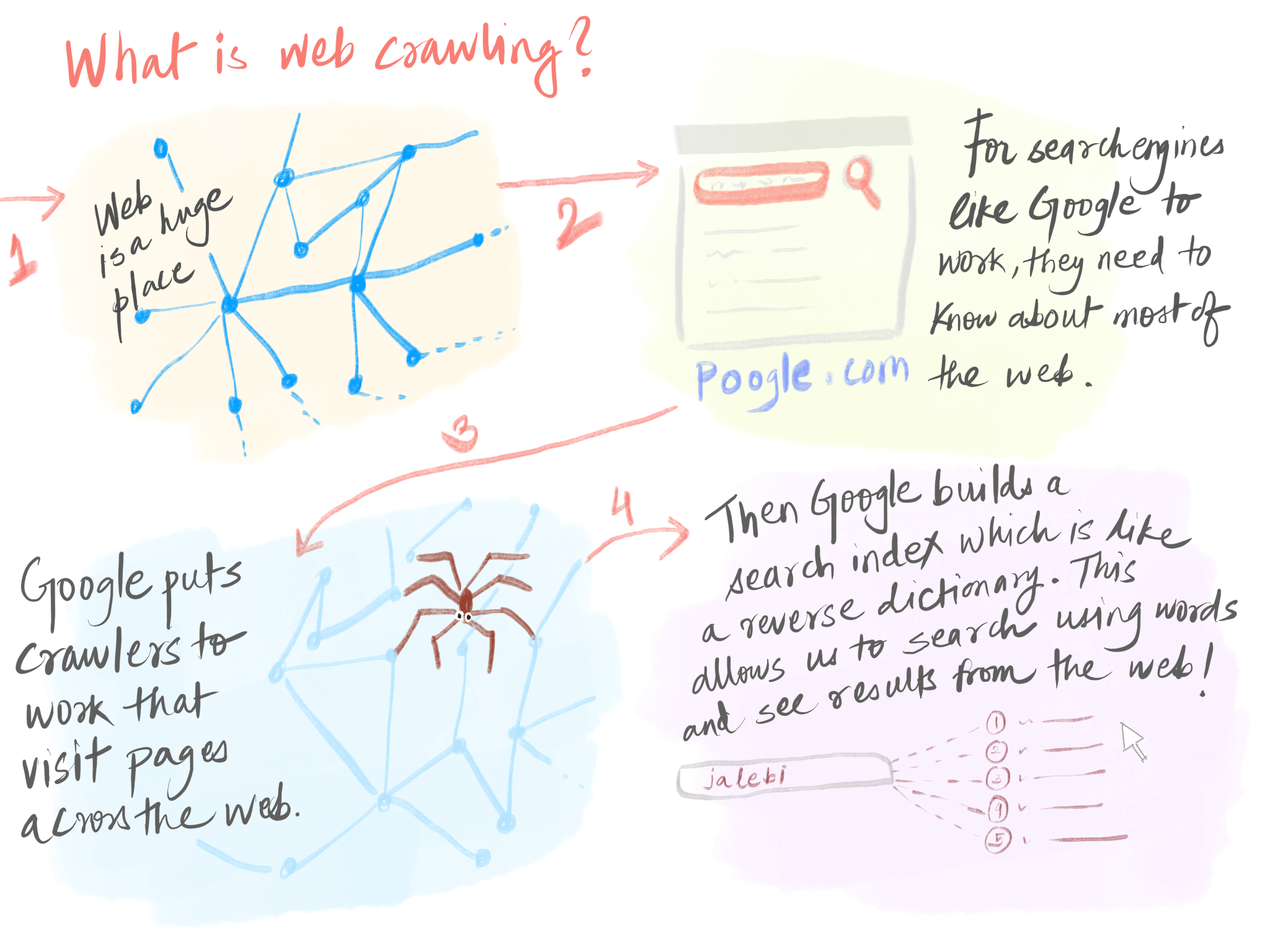

What is a web crawler? #

Here's a short diagram of what a crawler does. It is called a crawler because - the web! This program traverses the web in order to visit as many parts of it as possible.

Recently, I was going through a few graph problems and also was reading about a few system implementations. One of them was of a web crawler. Web, for me, is an interesting world. It is a complex network of infinite links connected with each other in numerous ways - it possibly can be called as the earliest and most evolved 'social network' of computers. In fact the nomenclature was derived the other way round.

Building a web crawler would be an interesting thing, and I think this is a common project that students pick up in college. For me, it is interesting because the possibilities are limitless - the web is huge. Even if I start at one corner, I should be able to cover a large portion just by following links going out of the pages. So here's how a simple web crawler would look like.

Web is a huge graph. So if we try to traverse it, we would be able to visit nodes present on the web. For traversal, we can use BFS as we want to cover the width of the graph and go as wide as possible. A BFS implementation includes a queue which stores all the child nodes of a particular visited node and the crawler logic keeps running until the queue becomes empty.

const bfs = (node, visit) => {

let queue = [node];

while (queue.length) {

let first = queue.shift();

if (!node.visited) {

visit(first);

queue.push(...node.children);

}

}

};A basic implementation of the crawler would include an in-memory array for the crawl queue. But if you can imagine, the size of this array can increase very rapidly and we might soon reach the JS heap limit. Another reason not to maintain it in memory is the restriction it puts while using multiple threads for crawling. At scale, you wouldn't run a single instance of the crawler as it will take a large amount of time to traverse even a tiny portion of the web. Since crawling is something that can be done parallely, given we maintain a track of visited links, we can easily deploy multiple instances of crawler visiting links and using a shared queue.

This is a perfect usecase for a message queue, something like Rabbitmq. I'll use Redis to keep things simple as it provides greats data structures for a queue. Redis can also be used to maintain the 'visited' hash map as it is a key-value storage at its core.

Once we visit a link, we will also store the contents of the link to be processed later. Before saving it, we will pull out all the links present on the page - these are the neighbouring nodes of the link in the web graph. We'll push them to the queue given we haven't visited them earlier and then the crawler will take care of the rest. To save the link content, we'll use MongoDB - a good place to dump unstructured data. Later, we can think of using this data to build an index for us to be able to search over the content.

My CrawlQueue looks as follows:

const { EventEmitter } = require('events');

// Assume all Redis API is promisified and available as functions

class CrawlQueue extends EventEmitter {

constructor(init) {

super();

init &&

init.forEach((u) => {

this.add(u);

});

}

async dequeue() {

let size = await this.size();

return !size ? null : await lpop();

}

async size() {

return await llen();

}

async peek() {

let size = await this.size();

return !size ? null : await lfirst();

}

async add(url) {

if ((await hget(url)) == '1') return;

await rpush(url);

await hset(url, '1');

await this.log();

if ((await this.size()) === 1) this.emit('pull');

}

async log() {

console.log('URLs in queue: ', await this.size());

}

}

module.exports = CrawlQueue;Internally, the queue uses Redis to store the URLs. For this experiment, I started from my own website - mohitkarekar.com. I was surprised to see how large the graph was when I ran this for a few seconds. In a famous paper by Andrei Broder and others (2001), the web graph is described to have a bowtie structure. This means that it is made up of a single strongly connected component which has a group of incoming links and another group of outgoing links - forming a shape similar to a bowtie. There are also a few smaller SCCs that are disconnected from the main component.

I am not sure where my website lies in this structure, but I'll try to reach upto a considerable radius outwards. In about 30 seconds the crawler could visit around 6000 links and then asynchronously process them and dump their content in MongoDB. Let's try this again with multiple threads.

// Crawler

const run = async (mongoClient) => {

const CrawlQueue = require('./crawlQueue');

let queue = new CrawlQueue();

const database = mongoClient.db('drstrange');

const crawlsDb = database.collection('crawls');

let stop = false;

const pull = async () => {

while ((await queue.size()) > 0) {

let url = await queue.dequeue();

// crawl visits the URL and extracts the embedded links in the page

crawl(url, crawlsDb)

.then(async (links) => {

if ((await queue.size()) > 2000) {

stop = true;

return;

} else {

if (stop) stop = false;

}

!stop &&

links.forEach((link) => {

queue.add(link);

});

})

.catch(() => {});

}

};

await pull();

};To run this code parallely, I'm using Node's cluster module. On my Macbook this would mean that 8 worker processes would run in parallel. I set a limit for 50000 items in the queue and ran this code, it took around 4 minutes 30 seconds to enqueue 50000 links and additional 30 minutes to visit each one of them. I ran into a few errors but since I'm using Redis, the queue is persisted even if my server crashes, given I don't shut down Redis itself. So I can easily restart the Node process and it will start off from where it had ended.

Above is an extensive diagram (which still might be incomplete) of a crawler at scale. The crawling and processing steps are decoupled as they can happen asynchronously. We maintain a separate queue for URLs that have been crawled and need to be processed. The 'Processor' service picks these up and saves them to MongoDB and also adds them to an Elasticsearch instance which would later support searching.

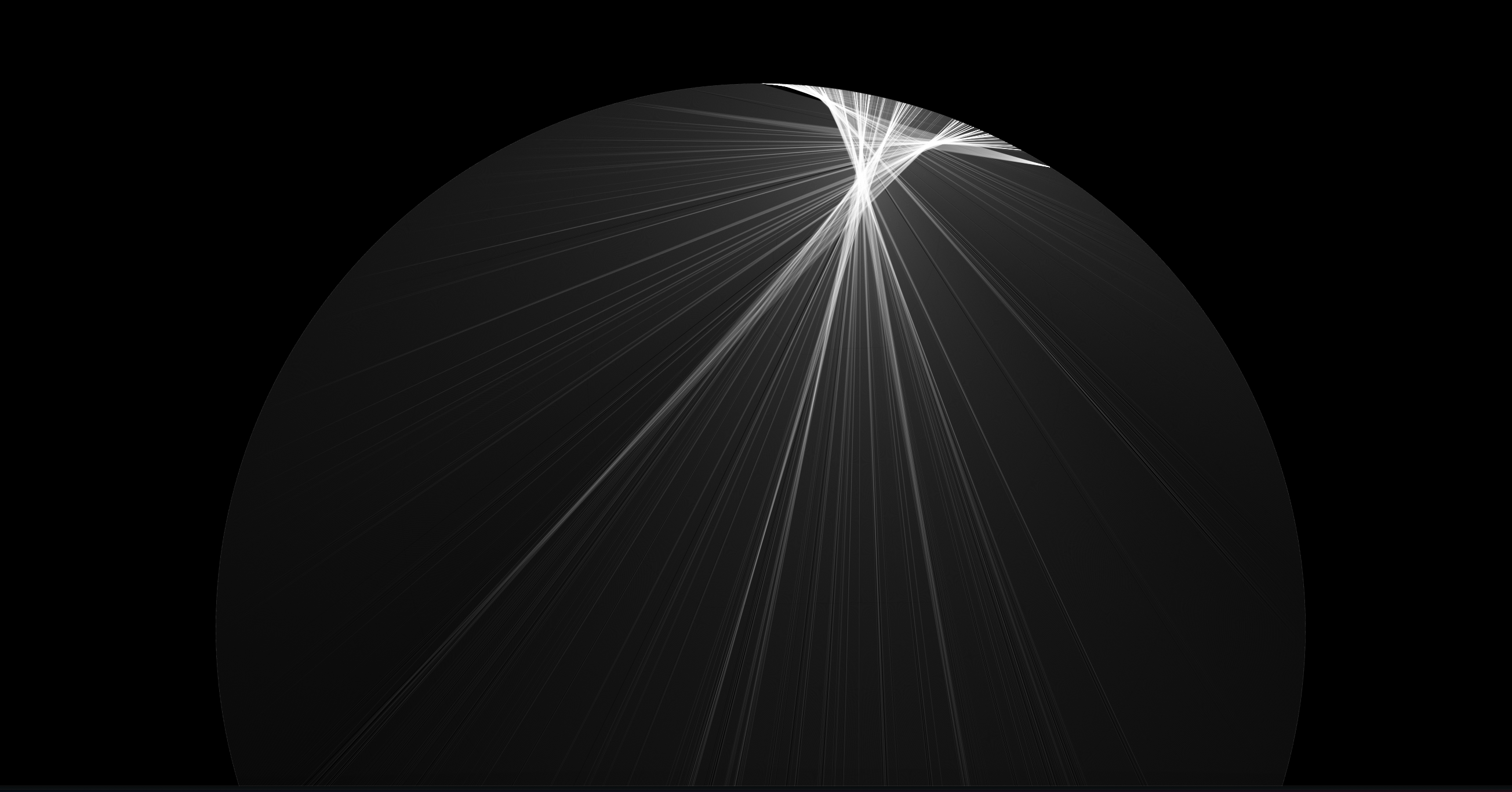

To beautify things, I also kept a track of the parent-child relationship for each link and then built a visualization which turned out to be beautiful!

This is a circular layout in Cytoscape. The dense area on the top denote the links that have several links going outwards. This set of links do not contain nodes that have several links coming inwards, I might have to explore farther. This was a good, fun exercise which has in the end left me with a large amount of crawled data; I might process this into something meaningful. I hope you enjoyed reading and could relate an algorithm to a more practical example.