Debouncing is a commonly discussed concept in a frontend interview. I was once asked about it, and back then I had no idea what it was. After using it in a project, I understood it well, it just struck how useful it was. Overall it is a simple concept but proves to be very crucial in terms of preventing unnecessary work.

It would be unfair to define debouncing directly. The best way to understand it is via the example of incremental search on the frontend. It is a high chance that at some point in your frontend career you would have to implement an instant search bar, where you'd have to list the results as the user types in the query string. A naive approach to this would be using the keyup event or onChange prop in case of React, which give you the current value of the input box.

<input id="search" />

<script>

const s = document.querySelector('#search');

s.addEventListener('keyup', () => {

const value = s.value;

fetch(`https://myapi.com/products?query=${value}`)

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((res) => {

displayResults(res);

});

});

</script>This implementation would work as expected, there is one chance of improvement here though. Let's consider the user searches for javascript, this code would fire 10 API requests, each with a query parameter equal to one letter added to the previous query.

GET https://myapi.com/products?query=j

GET https://myapi.com/products?query=ja

GET https://myapi.com/products?query=jav

.

.

GET https://myapi.com/products?query=javascrip

GET https://myapi.com/products?query=javascriptEach request would return and you would set the result list those many times. A much bigger problem is not for the frontend, but for the server handling these requests. Consider your app grows to a user base of a million, a magical situation! Now, a million users would be hitting your server with several such requests and there is a large chance that your server would get stuck doing trivial searches instead of catering to crucial APIs.

The main thing here is that to perform a search operation, you do not need the result of every substring that user types in. The search results for javas, javasc and javascr would largely be the same. You can avoid fetching results for these intermediate strings by implementing debouncing in your search logic.

Debouncing leverages the fact that we, humans, type at a certain speed, and depending on the time between two keystrokes one can easily deduce whether the user has finished typing what they had in their mind or they are yet to complete it. To search for a string, we would fire a request only when there has been no new keystroke for a certain specified time, assuming that this time limit is the one that determines that the user has completed typing the query.

In code, debounce would look like this:

const debounce = (func, ctx, timeout = 700) => {

let timer;

return (...args) => {

if (timer) clearTimeout(timer);

timer = setTimeout(() => {

func.call(ctx, ...args);

}, timeout);

};

};

const search = (value) => {

fetch(`https://myapi.com/products?query=${value}`)

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((res) => {

displayResults(res);

});

};

const searchDebounced = debounce(search, this);

searchDebounced('javas');

searchDebounced('javasc');

searchDebounced('javascr');

searchDebounced('javascri');

// API will be called only once with query = 'javascri'This is an elegant way to minimise work and save unnecesary API calls. This concept isn't limited to API calls and the frontend though. Debouncing can be applied anywhere where same repeated calls happen over time and instead of executing all of them, we only execute one in the end.

# Debouncing Jobs

A few months back I was working on an interesting task at upGrad, where we had to implement a queueing mechanism for generating sprites on our Node server. We have a data-driven marketing platform which is maintained using an inhouse CMS which allows editing and creating pages. Icons, logos and several other images are served in the form of a sprite which is generated on a page basis. I wouldn't go into details of how things are structured, but only that whenever any page is edited, and if any new images were added, our server would have to churn up a new sprite image.

Now, to ones who are unfamiliar with sprites, these are collection of several images alligned in a particular fashion in a single image. So for example, if your page had 10 logo images, 5 illustrated icons and 2 profile images, when the page sprite is generated, it would finally be a single png image with all these individual images placed together. When this image is loaded on the client, each individual image is accessed using the background-position property of CSS. Sprites are a great optimisation on the frontend in terms of reduced image requests.

The reason for implementing a queue was pretty straightforward - sprite generation process is intensive. It involves downloading the required images in memory and then generating an image out of it. When such a process was run in bulk for several pages, even after the process being asynchronous, led to a huge spike in CPU usage and sometimes memory limits hitting the peak. This affected the other APIs and also increased the risk of main process exiting.

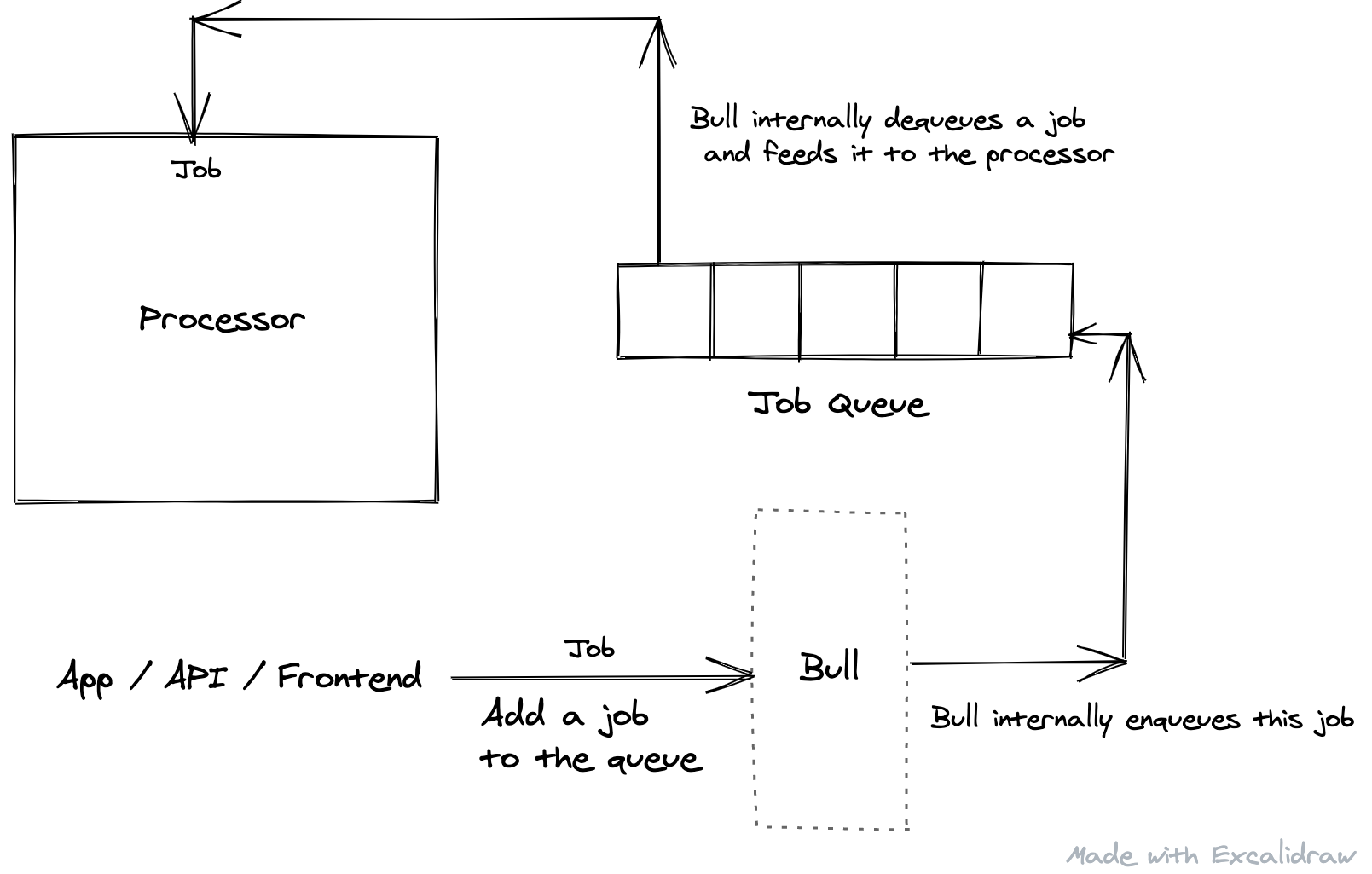

To implement the queue, we used Bull, a package which provides a rich queue interface and several features with it. The way it works is you create a queue, and define a processor function which performs the required operation. Whenever you call queue.add(job), Bull pushes the job to the queue and the processor is executed whenever the worker is free to do so. The processor can be executed in the main thread itself, or can be executed in a separate child process. Another important feature of Bull is that it runs every job in a sandboxed environment, hence preventing its failure affecting the main process.

For our particular implementation, it worked like this:

The flow starts when the app instructs Bull to add a job to the queue. Bull enqueues the job, irrespective of whether it is processing a job already. Whenever it is done processing jobs scheduled before the current one, it picks up the job and feeds it to the processor.

One important aspect of this flow is when another request to add a job comes when Bull has already enqueued a job. Since Bull is context-free of the kind of job, it simply adds it to the queue to be processed in line. The problem with this approach was that - keeping in mind as mentioned earlier that the jobs were run to generate a sprite for a particular page - if a request to generate a sprite came after a job was already added for the same page, it would lead to Bull processing those many jobs for the same sprite generation operation, which could have ideally been run only once.

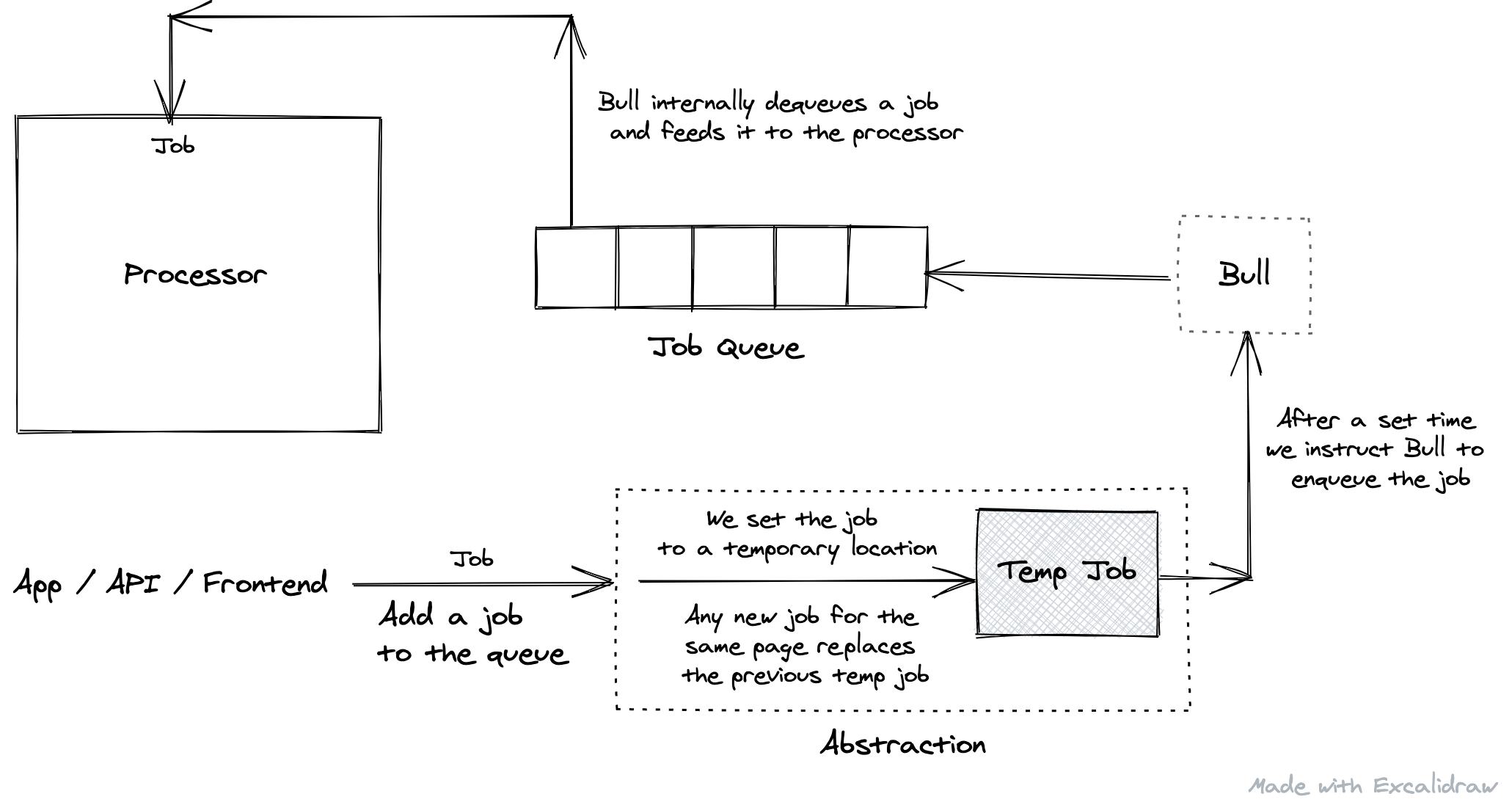

This is the same problem which we faced earlier, in case of the search input. And so is the solution for this - debouncing. We had to debounce the adding of the job to the queue, untill there was no new request to do the same for some limited time interval.

To acheive this, an abstraction was added before the step where the job was added to the queue. Whenever a request came in to add a job, it was first set to a temporary key in Redis. Any existing timeouts would be cleared and a new timeout would be scheduled, for say 10 seconds, to pickup the job from the temporary position and add it to the queue. So if another request came in for the same page, it would replace the Redis value. Finally when there are no new add jobs requests, we would add the job the queue.

The reason to use Redis was to have sustainability, in case of server going down and new requests coming in, keeping the temporary job in-memory would erase the request forever. Also, Redis is fast, so is almost like in-memory. This though, needs a supplementary start-up script to check if there are any temporary jobs present in Redis, and if yes, add them to the respective queues to be executed.

This method saves multiple job processes and kind of squashes them into a single call. It is interesting how such a simple concept can be so helpful at various places.